Monday, February 26, 2007

Why didn't i think of that?

This tip is bloody obvious... a must-have SOP for footcare while racing. Taken off the Mandatorygear.com website:

When applying hydropel or alternate foot salve:

- take one of your socks and turn it inside out

- put your hand inside the sock

- apply the salve to the sock or on your foot directly

- now rub the salve onto your foot with your hand inside the sock

- flip sock back to normal and put it on

Any additional unused salve is also on your foot and not on your hands, user beware of this tip with wholes in your socks!

-dan

When applying hydropel or alternate foot salve:

- take one of your socks and turn it inside out

- put your hand inside the sock

- apply the salve to the sock or on your foot directly

- now rub the salve onto your foot with your hand inside the sock

- flip sock back to normal and put it on

Any additional unused salve is also on your foot and not on your hands, user beware of this tip with wholes in your socks!

-dan

Thursday, February 22, 2007

The higher the peaks, the deeper the troughs

I'm in the off-season now, of course. Just that i have been itching to get out and DO STUFF. It's nice to have unstructured activity after 10 months. Physically i feel fine, but there are long-term benefits to be had by laying off for at least 3 weeks more. And of course, mentaly, i am looking for some new stimulus, but i must be careful that that does not cause me too much anxiety. Time to languish in the trough of slacker-dom and nuah-ness. I'm trying, i really am, but it is not easy.

Of course, not all that easy to do. Last weekend, did an 8-hour MTB relay race... this weekend, a MTB navigation training trip is on the cards. And i'm still find myself on the internet researching races to do, rigging my bike for Sabah (it is frigging 1.5 months away!), typing gear lists, compiling articles, and all that miscellaneous crap that keeps reminding me how much AR has become part of my nature. I'd really love to share my experiences, but i also need my time out here.

The business about SART becoming registered, the fracas about AR certification, forming lesson plans for AR training, and the general worrying about the state of conditioning of my team mates back home... just add to the mental and emotional load i am trying to get off my shoulder, post-season.

Guess i am the eternal visionary, but also the eternal worrier.

Of course, not all that easy to do. Last weekend, did an 8-hour MTB relay race... this weekend, a MTB navigation training trip is on the cards. And i'm still find myself on the internet researching races to do, rigging my bike for Sabah (it is frigging 1.5 months away!), typing gear lists, compiling articles, and all that miscellaneous crap that keeps reminding me how much AR has become part of my nature. I'd really love to share my experiences, but i also need my time out here.

The business about SART becoming registered, the fracas about AR certification, forming lesson plans for AR training, and the general worrying about the state of conditioning of my team mates back home... just add to the mental and emotional load i am trying to get off my shoulder, post-season.

Guess i am the eternal visionary, but also the eternal worrier.

Monday, February 19, 2007

Ironman vs. Coast to Coast - Epilogue

Epilogue – Comparisons, Reflections, and Acknowledgements

Coast to Coast boasts of itself as the World Championship for multisport; and while the same can be said for Kona where triathlon is concerned, I admittedly have yet to experience first-hand the madness that is racing the Ironman distance on ‘The Big Island’ where the whole ‘multisport’ scene was said to have begun. Will I qualify for that on my next Ironman race? Only the future will tell.

For what it is worth, determining which is the tougher race is like comparing apples and oranges. The demands of Ironman triathlon are quite set apart from the demands of a race like the Longest Day. The Ironman has a global appeal and reach, with a deeply talented pool of international athletes that knows no peer, while the Coast to Coast has a niche following and a more exclusive circle of top athletes in the Longest Day category. I would say the Ironman requires a higher threshold of mental focus due to the monotony of the repetitive movement it demands, but the Longest Day requires more situational awareness and alertness due to the dynamic and unpredictable nature of its setting. Coast to Coast is by far more logistically complex than the Ironman. Still, the appeal of Ironman lies in its ease of transferability across myriad race locations the world over, many of them beautiful and exotic. Ironman, in fact triathlon in general, has an established global authority that has seen huge success bringing its race into the international consciousness. Yet, in comparison, the Coast to Coast and the myriad multisport races of similar ilk retain their own special brand of grassroots involvement at no disadvantage whatsoever. Each race is beautiful in its own mode of appeal to its captive audience.

Both triathlon and multisport have seen huge advances in equipment technology, nutrition, and sports racing/coaching trends over the past two decades. The pinnacle of these developments can be seen year-to-year when the top athletes and the big brands they represent go head-to-head in their respective marquee events: Time trial bikes and racing kayaks utilizing the latest composite materials; the latest in fabric technology for wetsuits and racing apparel; innovative paraphernalia from shoelaces to helmets to hydration systems designed to shave weight, save time, and improve comfort & efficiency. Truly, the modern athlete is spoilt for choice - compared to the pioneers of yesteryear - as far as equipment is concerned.

With all my snazzy sports equipment now lying largely un-used and in need of servicing at the end of my season, and upon taking up a personal retrospection, I realize that finishing an Ironman/Coast to Coast double was not all smooth sailing. The race themselves were not as hard as the training I had to devote to them. Many a time I found myself unmotivated and reluctant to kick myself out of bed for the early morning sessions. Or I would hold off starting the day’s training to the point that when I did start a session in the afternoon, it dragged on into the night. And the perennial mind games would manifest themselves in a different form, and the voices in the head would be saying: you need your rest, don’t overdo yourself, you can take it easy to come back stronger next time.

Sometimes the voices were right, but only sometimes. I could take comfort in the fact that I would never have such an opportunity to train back in Singapore; that I was very fortunate to be training with athletes who were consistently more experienced, fitter and skilled than myself (and yet also very friendly and down-to-earth); and that while others were enjoying a period of ‘off’ during the year-end holiday season, I was pushing the envelope just a little more. I’m sure more than a few of my friends thought I was living like a hermit at the peak of my training.

Injuries (plus all the niggling strains, over-reaching, and ‘under-the-weather’ periods that come with the sport) were thankfully non-permanent. I realized that I stood to learn more from failure than success, and there were plenty of times where I had to adjust my approach to subsequent trainings, based on past shortcomings or deficiencies. Even the fact that the Ironman was before Coast to Coast meant that my lead-up to the latter could have been much better in terms of specificity and conditioning if the former was not on the cards… but then there is always next time, eh? It would be healthier to concentrate on one race only next season, and not squeeze in two within a couple of months, as I just did.

Every mistake made is a chance to not repeat it in future, as far as self-improvement goes. I felt blunt and groveled on certain parts of both races, but extremely good at other points – essentially, an emotional roller-coaster ride into the unknown, something inevitably experienced when undertaking any intense endeavour for the first time. As a relative novice to triathlon and multisport, management of these aspects would be learned only through conditioning and consistent exposure.

I believe I never lost sight of the big picture. There is always the next race, season, or year to aim for – longevity of interest and all of that. There is more to come for my adventure racing career. As they say, the journey has only just begun.

There are many people to whom I owe huge amounts of gratitude for their support.

Firstly, my coach Simon Knowles: without his guidance, advice, and drive, I’d still be a drowned rat (literally, in the swim; and figuratively, across the other key disciplines). Mentorship is such an important part of athletic development, and nowhere was that more apparent than throughout the past season under ‘Knowlesy’.

To my support crews on both races: Aunty Mui Lai (Ironman) and the Cameron family of Christchurch (Coast to Coast). My sincerest thanks for selflessly putting up with all the food woes, transport hassles, logistical nightmares, and general rushing around on otherwise peaceful weekends. I still feel I have not made it up to you sufficiently.

The Melbourne Adventure Club has been as good as family to me. I would especially like to thank the following people: Rachael Hutchins and Gill Hillton as superb INSPIRATIONS for Ironman and Coast to Coast respectively; Mark Bubner and Brendan Hills for the lessons in having a FAIR GO; Paul Simpson for CONCENTRATION ON THE RUN; Keith Falconer in keeping me HONEST; Pete Lockett, Kelly Linden and Delyth Lloyd for the laughs and BOUNDLESS enthusiasm; Kyle Naish and Jacqui Hickey for encouraging me to GO hard on the roadie sessions; Alex Kiendl in demonstrating what it takes to be TOUGH; Jarad Kohlar as a shining example on how to LOVE the trails; and Kath Copland for reminding me about my ROOTS in AR.

To my numerous team mates, friends, and competitors back home in Singapore: you guys provided the spark and stoked the fire, and keep me going still. I miss you lot, but I have been thinking about you always - even when dragging myself out of bed at 4 am to begin training on cold, wet winter mornings; picking the dirt and torn skin from fresh wounds after a mountain bike stack; or getting hammered mid-way through an AT/VO2max set. My cheers and congratulations go out to the fellow competitors I was lucky enough to make friends with in Busselton as well as in Christchurch. You guys are true inspirations, and tough as nails too.

I am indebted to Mum, Dad, and my sister Amanda – without your support and encouragement from afar, I would not have been able to get going in the first place. Finally, to all the people I have forgotten to mention: you know who you are.

I believe no one gets anywhere just by chance or coincidence. It has been a privilege to have you contribute – however seemingly short the time or insignificant the interaction - in one way or another, to the happy achievement of my Ironman and Coast to Coast double.

Coast to Coast boasts of itself as the World Championship for multisport; and while the same can be said for Kona where triathlon is concerned, I admittedly have yet to experience first-hand the madness that is racing the Ironman distance on ‘The Big Island’ where the whole ‘multisport’ scene was said to have begun. Will I qualify for that on my next Ironman race? Only the future will tell.

For what it is worth, determining which is the tougher race is like comparing apples and oranges. The demands of Ironman triathlon are quite set apart from the demands of a race like the Longest Day. The Ironman has a global appeal and reach, with a deeply talented pool of international athletes that knows no peer, while the Coast to Coast has a niche following and a more exclusive circle of top athletes in the Longest Day category. I would say the Ironman requires a higher threshold of mental focus due to the monotony of the repetitive movement it demands, but the Longest Day requires more situational awareness and alertness due to the dynamic and unpredictable nature of its setting. Coast to Coast is by far more logistically complex than the Ironman. Still, the appeal of Ironman lies in its ease of transferability across myriad race locations the world over, many of them beautiful and exotic. Ironman, in fact triathlon in general, has an established global authority that has seen huge success bringing its race into the international consciousness. Yet, in comparison, the Coast to Coast and the myriad multisport races of similar ilk retain their own special brand of grassroots involvement at no disadvantage whatsoever. Each race is beautiful in its own mode of appeal to its captive audience.

Both triathlon and multisport have seen huge advances in equipment technology, nutrition, and sports racing/coaching trends over the past two decades. The pinnacle of these developments can be seen year-to-year when the top athletes and the big brands they represent go head-to-head in their respective marquee events: Time trial bikes and racing kayaks utilizing the latest composite materials; the latest in fabric technology for wetsuits and racing apparel; innovative paraphernalia from shoelaces to helmets to hydration systems designed to shave weight, save time, and improve comfort & efficiency. Truly, the modern athlete is spoilt for choice - compared to the pioneers of yesteryear - as far as equipment is concerned.

With all my snazzy sports equipment now lying largely un-used and in need of servicing at the end of my season, and upon taking up a personal retrospection, I realize that finishing an Ironman/Coast to Coast double was not all smooth sailing. The race themselves were not as hard as the training I had to devote to them. Many a time I found myself unmotivated and reluctant to kick myself out of bed for the early morning sessions. Or I would hold off starting the day’s training to the point that when I did start a session in the afternoon, it dragged on into the night. And the perennial mind games would manifest themselves in a different form, and the voices in the head would be saying: you need your rest, don’t overdo yourself, you can take it easy to come back stronger next time.

Sometimes the voices were right, but only sometimes. I could take comfort in the fact that I would never have such an opportunity to train back in Singapore; that I was very fortunate to be training with athletes who were consistently more experienced, fitter and skilled than myself (and yet also very friendly and down-to-earth); and that while others were enjoying a period of ‘off’ during the year-end holiday season, I was pushing the envelope just a little more. I’m sure more than a few of my friends thought I was living like a hermit at the peak of my training.

Injuries (plus all the niggling strains, over-reaching, and ‘under-the-weather’ periods that come with the sport) were thankfully non-permanent. I realized that I stood to learn more from failure than success, and there were plenty of times where I had to adjust my approach to subsequent trainings, based on past shortcomings or deficiencies. Even the fact that the Ironman was before Coast to Coast meant that my lead-up to the latter could have been much better in terms of specificity and conditioning if the former was not on the cards… but then there is always next time, eh? It would be healthier to concentrate on one race only next season, and not squeeze in two within a couple of months, as I just did.

Every mistake made is a chance to not repeat it in future, as far as self-improvement goes. I felt blunt and groveled on certain parts of both races, but extremely good at other points – essentially, an emotional roller-coaster ride into the unknown, something inevitably experienced when undertaking any intense endeavour for the first time. As a relative novice to triathlon and multisport, management of these aspects would be learned only through conditioning and consistent exposure.

I believe I never lost sight of the big picture. There is always the next race, season, or year to aim for – longevity of interest and all of that. There is more to come for my adventure racing career. As they say, the journey has only just begun.

There are many people to whom I owe huge amounts of gratitude for their support.

Firstly, my coach Simon Knowles: without his guidance, advice, and drive, I’d still be a drowned rat (literally, in the swim; and figuratively, across the other key disciplines). Mentorship is such an important part of athletic development, and nowhere was that more apparent than throughout the past season under ‘Knowlesy’.

To my support crews on both races: Aunty Mui Lai (Ironman) and the Cameron family of Christchurch (Coast to Coast). My sincerest thanks for selflessly putting up with all the food woes, transport hassles, logistical nightmares, and general rushing around on otherwise peaceful weekends. I still feel I have not made it up to you sufficiently.

The Melbourne Adventure Club has been as good as family to me. I would especially like to thank the following people: Rachael Hutchins and Gill Hillton as superb INSPIRATIONS for Ironman and Coast to Coast respectively; Mark Bubner and Brendan Hills for the lessons in having a FAIR GO; Paul Simpson for CONCENTRATION ON THE RUN; Keith Falconer in keeping me HONEST; Pete Lockett, Kelly Linden and Delyth Lloyd for the laughs and BOUNDLESS enthusiasm; Kyle Naish and Jacqui Hickey for encouraging me to GO hard on the roadie sessions; Alex Kiendl in demonstrating what it takes to be TOUGH; Jarad Kohlar as a shining example on how to LOVE the trails; and Kath Copland for reminding me about my ROOTS in AR.

To my numerous team mates, friends, and competitors back home in Singapore: you guys provided the spark and stoked the fire, and keep me going still. I miss you lot, but I have been thinking about you always - even when dragging myself out of bed at 4 am to begin training on cold, wet winter mornings; picking the dirt and torn skin from fresh wounds after a mountain bike stack; or getting hammered mid-way through an AT/VO2max set. My cheers and congratulations go out to the fellow competitors I was lucky enough to make friends with in Busselton as well as in Christchurch. You guys are true inspirations, and tough as nails too.

I am indebted to Mum, Dad, and my sister Amanda – without your support and encouragement from afar, I would not have been able to get going in the first place. Finally, to all the people I have forgotten to mention: you know who you are.

I believe no one gets anywhere just by chance or coincidence. It has been a privilege to have you contribute – however seemingly short the time or insignificant the interaction - in one way or another, to the happy achievement of my Ironman and Coast to Coast double.

Ironman vs. Coast to Coast: Part 3

...Part 3

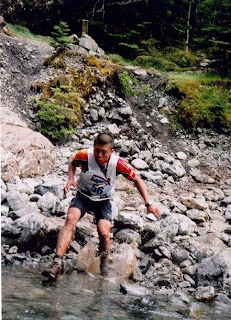

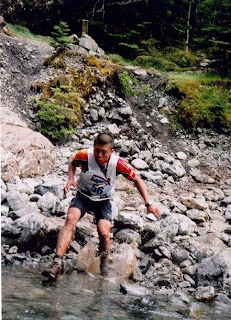

I had written down, using a waterproof marker, reminders of landmarks to look out for on the run up the Deception Valley – scrawled on my left forearm. Well, I can safely say I took all the correct routes up till the point the ink started fading – somewhere past my wrist and the back of my hand (thanks to numerous water crossings and instinctive wiping of sweat). My gains in time from picking the sneaky little bush tracks above the notorious Big Boulders section of the route turned to custard. I was stuck with a bluff in front of me, and had to take a corrective swim across a deep pool to re-join the trail proper. As I floundered in the cold water, six runners who I thought I had the jump on passed right before my eyes. Rats.

There was a price to pay for going harder than necessary with this continual running, climbing, and drenching in cold water - all the while gaining altitude with falling temperatures. Upon cresting Goat Pass and descending into the Mingha Valley, my downhill muscles were unable to work. My coordination was all delayed, my legs flip-flopping uselessly like marionette limbs, and I had to run more gently than I would have liked to avoid doing a faceplant into the rock-strewn trail. A deep ache started up in my hips. I knew this was all the consequence of insufficient conditioning. More runners passed me. Eventually, the boggiest sections of the run came up, and while I had recovered some of my coordination, my energy levels were dropping due to insufficient food. I rationed my remaining two gels and my energy bar, but to no avail. Heading out onto the last riverbed run, I began bonking as the soles of my feet started to protest in pain.

People continued passing me. These folks, I reasoned, likely regarded training in such spectacularly rugged and demanding conditions as run-of-the-mill. I found new respect for every single New Zealand-conditioned athlete on the course. The transition in the distance seemed to take forever to reach, so it was with great relief that I hauled myself up the concrete blocks and into transition, the cries of “Go Singapore!” and “Come on, Wilson!” from scores of spectators ringing in my ears.

Having been ushered onto my bike by Barry, I proceeded to stuff my face with my lunch as I pedaled out onto the asphalt. This short 15km ride was fairly interesting, with flat sections as well as steep climbs and descents, but I managed to down all my food by the time I was waved into the end of this section by Iain.

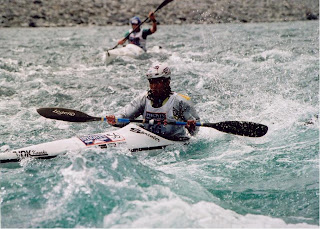

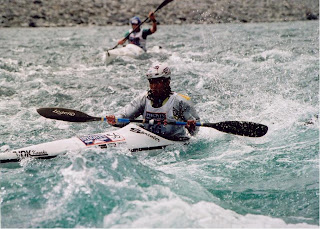

The kayak section was such a relief for my legs, and I quickly got into a rhythm. Scanning early for the right braids to take (with reference to notes written on my kayak foredeck), I looked forward to each rapid section. I know my core stability had taken a beating on the mountain run, so I was very cautious in terms of line selection through the rock gardens, bluff turns, eddies, and wave trains of the mighty Waimakariri River. Even then, I nearly came to grief a couple of times on some huge wave trains and eddies. I had Eskimo rolled in the Waimak earlier during a familiarization trip, but even with the reminder: “SET UP ROLL EARLY!” printed in bold across my foredeck, I was doubtful I could roll successfully if I flipped upside-down. Forlorn racers emptying their boats just downstream of gnarly sections were an occasional reminder of what awaited me if I messed up. Halfway through the gorge, I got out of the boat. My bottom was in agony, and my boat had several litres of water (and urine) sloshing around in it. Time to give myself a stretch and the boat an empty. Stretched, with my spray skirt re-adjusted and all water out of the hull, I continued downstream with renewed vigour.

I had Eskimo rolled in the Waimak earlier during a familiarization trip, but even with the reminder: “SET UP ROLL EARLY!” printed in bold across my foredeck, I was doubtful I could roll successfully if I flipped upside-down. Forlorn racers emptying their boats just downstream of gnarly sections were an occasional reminder of what awaited me if I messed up. Halfway through the gorge, I got out of the boat. My bottom was in agony, and my boat had several litres of water (and urine) sloshing around in it. Time to give myself a stretch and the boat an empty. Stretched, with my spray skirt re-adjusted and all water out of the hull, I continued downstream with renewed vigour.

Soon, the infamous ‘Rock’ loomed in front of me past a left-hand chute. Official advice had been to portage this section if in doubt, and a dozen safety personnel were positioned in kayaks, by the banks, and even atop the rock itself, ready to rescue any racer foolhardy enough to refuse portaging and subsequently capsizing here. The popular opinion was that this would be a favourite spot for event photographers, due to the amount of carnage that was expected. I spied a racer in a sea kayak pulling to the bank to portage, but I vowed that this would be my moment – my shot at glory. Considering all the earlier suffering, with heaps of competitors already ahead of me, and even if I groveled for the remainder of the race, I reasoned that if I cleared this rapid (even with an Eskimo roll thrown in, if it came to that), I would be totally satisfied with having ‘mastered The Rock’. I hung to the right, then like magic, I coasted to the side of the wave train that was smashing itself against this jagged grey-black mass… and passed it. I had done it. Ecstatic and tanked up on adrenalin, I shouted “Woo-hoo!” and grinned ear-to-ear.

The popular opinion was that this would be a favourite spot for event photographers, due to the amount of carnage that was expected. I spied a racer in a sea kayak pulling to the bank to portage, but I vowed that this would be my moment – my shot at glory. Considering all the earlier suffering, with heaps of competitors already ahead of me, and even if I groveled for the remainder of the race, I reasoned that if I cleared this rapid (even with an Eskimo roll thrown in, if it came to that), I would be totally satisfied with having ‘mastered The Rock’. I hung to the right, then like magic, I coasted to the side of the wave train that was smashing itself against this jagged grey-black mass… and passed it. I had done it. Ecstatic and tanked up on adrenalin, I shouted “Woo-hoo!” and grinned ear-to-ear.

The going got tougher, as was to be expected. My bottom was soon in so much pain that I had to lie back on the rear deck from time to time just to ease the pressure off it. My taste buds and stomach had had enough of Hammer Perpetuem sports drink, and I resorted to drinking river water instead (no doubt now having a higher concentration of urine than at any other time of the year) to wash down what remained of the fruit and energy bars stuck to my paddle shaft. I prayed for the end of the kayaking section, and heaved an audible sigh of relief when the bridge marking the transition area finally loomed overhead between two steep bluffs.

Iain, Barry and Lynda were ready for me. Iain bear-hugged me from behind, lifting me out of the cockpit and onto my barely functioning legs. The cold hit me hard, and Iain noticed this immediately. I deliberated, and then relented to put on a thermal top and beanie for the final ride. While Barry and Lynda took care of my kayak, Iain massaged my legs, fed me, then marched me up to the waiting bicycle. The first five minutes of the bike ride felt awful, with my front wheel wobbling all over the place as my upper body shivered uncontrollably in the aero position against a gentle but bitingly cold easterly wind. Boy was I glad to get warmed up with blood pumping through my legs again! I held a steady pace and rationed my ‘wake-up’ nutrition: two caffeine-added gels and a bottle full of Coca Cola. Along mind-numbing farmland roads and into the gathering dusk, I pedaled. My spirits were lifted as I spied the first traffic lights, but then the ‘red light’ sprints began as well. I could not be bothered at this point. My cycling movement was regressing into survival mode once more as the remnants of my energy ebbed from my body. I actually found myself yawning on the last stretch of road leading out of the city and towards Sumner. But I knew that it would all be over soon.

The first five minutes of the bike ride felt awful, with my front wheel wobbling all over the place as my upper body shivered uncontrollably in the aero position against a gentle but bitingly cold easterly wind. Boy was I glad to get warmed up with blood pumping through my legs again! I held a steady pace and rationed my ‘wake-up’ nutrition: two caffeine-added gels and a bottle full of Coca Cola. Along mind-numbing farmland roads and into the gathering dusk, I pedaled. My spirits were lifted as I spied the first traffic lights, but then the ‘red light’ sprints began as well. I could not be bothered at this point. My cycling movement was regressing into survival mode once more as the remnants of my energy ebbed from my body. I actually found myself yawning on the last stretch of road leading out of the city and towards Sumner. But I knew that it would all be over soon.

Finally, out of the gloom, officials to the left of the road, all smiles and cheers, waved me in and told me to dismount and proceed to the finish. I staggered off my bike, down the dark footway and onto the sand of Sumner Beach, the commentator blaring that I was the first Singaporean to attempt and complete the Longest Day. Amidst the glare of the finish line floodlights, I found myself with a finisher’s medal around my neck, a can of Speight’s in one hand, and the hand of Robin Judkins - the loud, eccentric director of this epic event – firmly gripping the other. The ordeal was over. Iain was there too to video the entire scene.

In the darkness, away from the cheering crowd, I smiled as I recollected my day, and the days, weeks, months, and years prior to this moment.

I could rest now.

I had written down, using a waterproof marker, reminders of landmarks to look out for on the run up the Deception Valley – scrawled on my left forearm. Well, I can safely say I took all the correct routes up till the point the ink started fading – somewhere past my wrist and the back of my hand (thanks to numerous water crossings and instinctive wiping of sweat). My gains in time from picking the sneaky little bush tracks above the notorious Big Boulders section of the route turned to custard. I was stuck with a bluff in front of me, and had to take a corrective swim across a deep pool to re-join the trail proper. As I floundered in the cold water, six runners who I thought I had the jump on passed right before my eyes. Rats.

There was a price to pay for going harder than necessary with this continual running, climbing, and drenching in cold water - all the while gaining altitude with falling temperatures. Upon cresting Goat Pass and descending into the Mingha Valley, my downhill muscles were unable to work. My coordination was all delayed, my legs flip-flopping uselessly like marionette limbs, and I had to run more gently than I would have liked to avoid doing a faceplant into the rock-strewn trail. A deep ache started up in my hips. I knew this was all the consequence of insufficient conditioning. More runners passed me. Eventually, the boggiest sections of the run came up, and while I had recovered some of my coordination, my energy levels were dropping due to insufficient food. I rationed my remaining two gels and my energy bar, but to no avail. Heading out onto the last riverbed run, I began bonking as the soles of my feet started to protest in pain.

People continued passing me. These folks, I reasoned, likely regarded training in such spectacularly rugged and demanding conditions as run-of-the-mill. I found new respect for every single New Zealand-conditioned athlete on the course. The transition in the distance seemed to take forever to reach, so it was with great relief that I hauled myself up the concrete blocks and into transition, the cries of “Go Singapore!” and “Come on, Wilson!” from scores of spectators ringing in my ears.

Having been ushered onto my bike by Barry, I proceeded to stuff my face with my lunch as I pedaled out onto the asphalt. This short 15km ride was fairly interesting, with flat sections as well as steep climbs and descents, but I managed to down all my food by the time I was waved into the end of this section by Iain.

The kayak section was such a relief for my legs, and I quickly got into a rhythm. Scanning early for the right braids to take (with reference to notes written on my kayak foredeck), I looked forward to each rapid section. I know my core stability had taken a beating on the mountain run, so I was very cautious in terms of line selection through the rock gardens, bluff turns, eddies, and wave trains of the mighty Waimakariri River. Even then, I nearly came to grief a couple of times on some huge wave trains and eddies.

I had Eskimo rolled in the Waimak earlier during a familiarization trip, but even with the reminder: “SET UP ROLL EARLY!” printed in bold across my foredeck, I was doubtful I could roll successfully if I flipped upside-down. Forlorn racers emptying their boats just downstream of gnarly sections were an occasional reminder of what awaited me if I messed up. Halfway through the gorge, I got out of the boat. My bottom was in agony, and my boat had several litres of water (and urine) sloshing around in it. Time to give myself a stretch and the boat an empty. Stretched, with my spray skirt re-adjusted and all water out of the hull, I continued downstream with renewed vigour.

I had Eskimo rolled in the Waimak earlier during a familiarization trip, but even with the reminder: “SET UP ROLL EARLY!” printed in bold across my foredeck, I was doubtful I could roll successfully if I flipped upside-down. Forlorn racers emptying their boats just downstream of gnarly sections were an occasional reminder of what awaited me if I messed up. Halfway through the gorge, I got out of the boat. My bottom was in agony, and my boat had several litres of water (and urine) sloshing around in it. Time to give myself a stretch and the boat an empty. Stretched, with my spray skirt re-adjusted and all water out of the hull, I continued downstream with renewed vigour.Soon, the infamous ‘Rock’ loomed in front of me past a left-hand chute. Official advice had been to portage this section if in doubt, and a dozen safety personnel were positioned in kayaks, by the banks, and even atop the rock itself, ready to rescue any racer foolhardy enough to refuse portaging and subsequently capsizing here.

The popular opinion was that this would be a favourite spot for event photographers, due to the amount of carnage that was expected. I spied a racer in a sea kayak pulling to the bank to portage, but I vowed that this would be my moment – my shot at glory. Considering all the earlier suffering, with heaps of competitors already ahead of me, and even if I groveled for the remainder of the race, I reasoned that if I cleared this rapid (even with an Eskimo roll thrown in, if it came to that), I would be totally satisfied with having ‘mastered The Rock’. I hung to the right, then like magic, I coasted to the side of the wave train that was smashing itself against this jagged grey-black mass… and passed it. I had done it. Ecstatic and tanked up on adrenalin, I shouted “Woo-hoo!” and grinned ear-to-ear.

The popular opinion was that this would be a favourite spot for event photographers, due to the amount of carnage that was expected. I spied a racer in a sea kayak pulling to the bank to portage, but I vowed that this would be my moment – my shot at glory. Considering all the earlier suffering, with heaps of competitors already ahead of me, and even if I groveled for the remainder of the race, I reasoned that if I cleared this rapid (even with an Eskimo roll thrown in, if it came to that), I would be totally satisfied with having ‘mastered The Rock’. I hung to the right, then like magic, I coasted to the side of the wave train that was smashing itself against this jagged grey-black mass… and passed it. I had done it. Ecstatic and tanked up on adrenalin, I shouted “Woo-hoo!” and grinned ear-to-ear.The going got tougher, as was to be expected. My bottom was soon in so much pain that I had to lie back on the rear deck from time to time just to ease the pressure off it. My taste buds and stomach had had enough of Hammer Perpetuem sports drink, and I resorted to drinking river water instead (no doubt now having a higher concentration of urine than at any other time of the year) to wash down what remained of the fruit and energy bars stuck to my paddle shaft. I prayed for the end of the kayaking section, and heaved an audible sigh of relief when the bridge marking the transition area finally loomed overhead between two steep bluffs.

Iain, Barry and Lynda were ready for me. Iain bear-hugged me from behind, lifting me out of the cockpit and onto my barely functioning legs. The cold hit me hard, and Iain noticed this immediately. I deliberated, and then relented to put on a thermal top and beanie for the final ride. While Barry and Lynda took care of my kayak, Iain massaged my legs, fed me, then marched me up to the waiting bicycle.

The first five minutes of the bike ride felt awful, with my front wheel wobbling all over the place as my upper body shivered uncontrollably in the aero position against a gentle but bitingly cold easterly wind. Boy was I glad to get warmed up with blood pumping through my legs again! I held a steady pace and rationed my ‘wake-up’ nutrition: two caffeine-added gels and a bottle full of Coca Cola. Along mind-numbing farmland roads and into the gathering dusk, I pedaled. My spirits were lifted as I spied the first traffic lights, but then the ‘red light’ sprints began as well. I could not be bothered at this point. My cycling movement was regressing into survival mode once more as the remnants of my energy ebbed from my body. I actually found myself yawning on the last stretch of road leading out of the city and towards Sumner. But I knew that it would all be over soon.

The first five minutes of the bike ride felt awful, with my front wheel wobbling all over the place as my upper body shivered uncontrollably in the aero position against a gentle but bitingly cold easterly wind. Boy was I glad to get warmed up with blood pumping through my legs again! I held a steady pace and rationed my ‘wake-up’ nutrition: two caffeine-added gels and a bottle full of Coca Cola. Along mind-numbing farmland roads and into the gathering dusk, I pedaled. My spirits were lifted as I spied the first traffic lights, but then the ‘red light’ sprints began as well. I could not be bothered at this point. My cycling movement was regressing into survival mode once more as the remnants of my energy ebbed from my body. I actually found myself yawning on the last stretch of road leading out of the city and towards Sumner. But I knew that it would all be over soon.Finally, out of the gloom, officials to the left of the road, all smiles and cheers, waved me in and told me to dismount and proceed to the finish. I staggered off my bike, down the dark footway and onto the sand of Sumner Beach, the commentator blaring that I was the first Singaporean to attempt and complete the Longest Day. Amidst the glare of the finish line floodlights, I found myself with a finisher’s medal around my neck, a can of Speight’s in one hand, and the hand of Robin Judkins - the loud, eccentric director of this epic event – firmly gripping the other. The ordeal was over. Iain was there too to video the entire scene.

In the darkness, away from the cheering crowd, I smiled as I recollected my day, and the days, weeks, months, and years prior to this moment.

I could rest now.

Ironman Vs. Coast to Coast: Part 2

Part 2

… Continued… To the Coast

I felt much less pressure going into the Coast to Coast than during the lead-up to Ironman WA, partly because I was the first Singaporean citizen to be attempting it as a Longest Day participant. It was hard not to adopt a holiday mood (I felt more ‘intense’ going into the Ironman at Busselton), but then again, I was in unknown territory here, so i might as well not stress too much about it. I realized it would be somewhat lonely, with no fellow countrymen to have a yarn with or to engage in a bit of friendly rivalry with. So I set about doing the next best thing: Making dozens of new friends during my Coast to Coast campaign.

The Longest Day

The aforementioned title for the one-day individual event of the Speight’s Coast to Coast is apt. World champion adventure racer Ian Adamson called this race ‘the proving ground for the world’s best adventure racers’. It is a race with its own unique quirks and ethos, with a cult-like following unlike any other endurance event, and mind-blowing scenery throughout. But the athletes who have attempted this great race all draw the same conclusion: it is a phenomenally tough event.

The logistical nightmare that was getting the competitor to the start line was a race in itself. Food, transportation, accommodation, and a myriad contingency plans had to be sorted out with the aid of a very integral part of the race effort – the support crew. For international athletes, the complexities of the lead-up were compounded. Friends and family either fly in to support them; or else crews had to be sourced locally, brought up to date, briefed, or otherwise bribed to accommodate the athlete come race day. I believed familiarization trips to check out the technical and potentially treacherous bits on the mountain run and kayak sections were almost mandatory for first-time overseas competitors. These trips were vital for participants who were more likely than not wholly unaccustomed to the demanding terrain and unpredictable conditions that constitute the race route.

Racing kayaks and the associated equipment had to be rented, tested, modified (or swapped), repaired (in the event of damage during training) and tested again. Then there were the bike bits, race nutrition, and other assorted gear that had to be prepped in such a way that the support crew could efficiently and methodically facilitate transitions, whilst possibly dealing with one blabbering, panicking, ranting, or otherwise very subdued athlete. The whole lot had to be convoyed across the South Island to the start; then, come race day, promptly transferred back again, leap-frog style, through the handful of remote transition areas. My crew of Iain and Barry were prepared as they could be, and would be waiting to swing into action at Aickens on race day.

In the half-light of race morning at Kumara Beach, I lined up at the start, glad to have settled all my preparation. The starting horn sounded soon enough, and we were off.

The opening 3km run before the 55km bike ride was infamous as a ‘gut-buster’. In their haste to get in with the first bunch of cyclists and not be left behind, everyone set a solid pace for the bike racks. The whole experience was not unlike the running of the bulls at Pamplona.

Hopping on my bike, my heart rate was well and truly in skyrocket territory. To get it down would not be the easiest thing to do, especially when you are pumped to the gills with adrenalin out of anxiety to hang in a peloton, and to be finally competing on the same stage as some of your favourite adventure racing idols!

I fell back. The effort was too much even trying to hang with the second bunch. The road inclined ever-so-slightly upwards, and that notorious easterly headwind was already out and about on this early Saturday morning as the sun crept over the peaks of the Main Divide ahead. The mountains were coming. Soon, I glimpsed a climbing turn in the distance before noticing some graffiti on the road, just in front of a farmhouse to the left. In typical poignant Kiwi humour, the fluorescent scribbling read: “Horrible hill ahead”.

A group of three eventually caught up with me. I was never comfortable riding in big groups, let alone a competitive peloton. To my disadvantage, I had to settle for something more manageable in size, and more importantly prevent blowing up so early in the race. The four of us took turns as the road gained height all the way till our first transition at Aickens.

Aickens is renowned for its chaotic transitions, particularly on the Two-Day event. Huge bunches coming into the chute amidst throngs of support crew and spectators made for utter bedlam. As a consolation, the four of us, having stayed behind the main bunches, made the transition fairly smoothly. Guided in by Barry and having had my gear swapped by Iain, it was onto the mountain run. I ate half a banana but dropped the other half (and did not bother to stop and pick it up and finish it off); and was demolishing my handful of pikelets when I came to the first river crossing. My pikelets carelessly swiped the water, and the next thing I knew I had a soggy lump of dough in my hand. This nutritional double faux pas would later prove to be a costly mistake.

I ate half a banana but dropped the other half (and did not bother to stop and pick it up and finish it off); and was demolishing my handful of pikelets when I came to the first river crossing. My pikelets carelessly swiped the water, and the next thing I knew I had a soggy lump of dough in my hand. This nutritional double faux pas would later prove to be a costly mistake.

To be continued...

… Continued… To the Coast

I felt much less pressure going into the Coast to Coast than during the lead-up to Ironman WA, partly because I was the first Singaporean citizen to be attempting it as a Longest Day participant. It was hard not to adopt a holiday mood (I felt more ‘intense’ going into the Ironman at Busselton), but then again, I was in unknown territory here, so i might as well not stress too much about it. I realized it would be somewhat lonely, with no fellow countrymen to have a yarn with or to engage in a bit of friendly rivalry with. So I set about doing the next best thing: Making dozens of new friends during my Coast to Coast campaign.

The Longest Day

The aforementioned title for the one-day individual event of the Speight’s Coast to Coast is apt. World champion adventure racer Ian Adamson called this race ‘the proving ground for the world’s best adventure racers’. It is a race with its own unique quirks and ethos, with a cult-like following unlike any other endurance event, and mind-blowing scenery throughout. But the athletes who have attempted this great race all draw the same conclusion: it is a phenomenally tough event.

The logistical nightmare that was getting the competitor to the start line was a race in itself. Food, transportation, accommodation, and a myriad contingency plans had to be sorted out with the aid of a very integral part of the race effort – the support crew. For international athletes, the complexities of the lead-up were compounded. Friends and family either fly in to support them; or else crews had to be sourced locally, brought up to date, briefed, or otherwise bribed to accommodate the athlete come race day. I believed familiarization trips to check out the technical and potentially treacherous bits on the mountain run and kayak sections were almost mandatory for first-time overseas competitors. These trips were vital for participants who were more likely than not wholly unaccustomed to the demanding terrain and unpredictable conditions that constitute the race route.

Racing kayaks and the associated equipment had to be rented, tested, modified (or swapped), repaired (in the event of damage during training) and tested again. Then there were the bike bits, race nutrition, and other assorted gear that had to be prepped in such a way that the support crew could efficiently and methodically facilitate transitions, whilst possibly dealing with one blabbering, panicking, ranting, or otherwise very subdued athlete. The whole lot had to be convoyed across the South Island to the start; then, come race day, promptly transferred back again, leap-frog style, through the handful of remote transition areas. My crew of Iain and Barry were prepared as they could be, and would be waiting to swing into action at Aickens on race day.

In the half-light of race morning at Kumara Beach, I lined up at the start, glad to have settled all my preparation. The starting horn sounded soon enough, and we were off.

The opening 3km run before the 55km bike ride was infamous as a ‘gut-buster’. In their haste to get in with the first bunch of cyclists and not be left behind, everyone set a solid pace for the bike racks. The whole experience was not unlike the running of the bulls at Pamplona.

Hopping on my bike, my heart rate was well and truly in skyrocket territory. To get it down would not be the easiest thing to do, especially when you are pumped to the gills with adrenalin out of anxiety to hang in a peloton, and to be finally competing on the same stage as some of your favourite adventure racing idols!

I fell back. The effort was too much even trying to hang with the second bunch. The road inclined ever-so-slightly upwards, and that notorious easterly headwind was already out and about on this early Saturday morning as the sun crept over the peaks of the Main Divide ahead. The mountains were coming. Soon, I glimpsed a climbing turn in the distance before noticing some graffiti on the road, just in front of a farmhouse to the left. In typical poignant Kiwi humour, the fluorescent scribbling read: “Horrible hill ahead”.

A group of three eventually caught up with me. I was never comfortable riding in big groups, let alone a competitive peloton. To my disadvantage, I had to settle for something more manageable in size, and more importantly prevent blowing up so early in the race. The four of us took turns as the road gained height all the way till our first transition at Aickens.

Aickens is renowned for its chaotic transitions, particularly on the Two-Day event. Huge bunches coming into the chute amidst throngs of support crew and spectators made for utter bedlam. As a consolation, the four of us, having stayed behind the main bunches, made the transition fairly smoothly. Guided in by Barry and having had my gear swapped by Iain, it was onto the mountain run.

I ate half a banana but dropped the other half (and did not bother to stop and pick it up and finish it off); and was demolishing my handful of pikelets when I came to the first river crossing. My pikelets carelessly swiped the water, and the next thing I knew I had a soggy lump of dough in my hand. This nutritional double faux pas would later prove to be a costly mistake.

I ate half a banana but dropped the other half (and did not bother to stop and pick it up and finish it off); and was demolishing my handful of pikelets when I came to the first river crossing. My pikelets carelessly swiped the water, and the next thing I knew I had a soggy lump of dough in my hand. This nutritional double faux pas would later prove to be a costly mistake.To be continued...

Saturday, February 17, 2007

A Day Like This – Ironman vs. Coast to Coast (Part 1)

“The biggest room in the world is the room for improvement.”

Prologue – Sizing Up

One race involves a mass open water swim, an 180km road bike time trial, and a full marathon, combined in a mind-boggling back-to-back format. The other boasts a backcountry course incorporating rural roads, mountain passes, and glacial rivers - spanning an island nation literally from coast to coast.

The Ironman triathlon and the Coast to Coast “Longest Day” multisport race: two endurance events, involving multiple disciplines, challenging the individual athlete, over a single day.

These two races are distinct from other well-known competitive endeavours of human endurance. There are single discipline events (like swimming the English Channel, ultramarathoning, and trans-ocean yacht racing) where total focus on a single skill set is required. There are the multi-day stage races (everything from week-long desert foot races to professional cycling tours like the Tour de France) that spread out the exertion over huge blocks of time, interspersed with sleep. And then there are team or relay events (as per adventure races and the hugely popular endurance mountain biking events) where an individual gets to be part of something more than just him/herself, and where the notion of “misery loves company” can be wholly realized.

Still, the Ironman and the Longest Day stand apart. They compress the fatigue and competition to within a single day, without rests or breaks – negating any opportunity to consolidate efforts or recover. They place the burden of the race effort upon the individual athlete – all the highs, lows, triumphs, and mistakes belong to him/her alone. And they demand that the single athlete – in order to just finish the race - be proficient across three disciplines and be able to make time cut-offs. These two events are truly the ultimate test in their respective endurance sports genres.

As an adventure racer on the look out for new challenges away from the team format for a change, I had always been intrigued to find out which race was the more difficult – the more grueling, arduous, and challenging. Only one way to find out: do them both.

Iron Will

The world championship for the Ironman race distance is held in Kona, on the big island of Hawaii, USA. As deemed by the triathlon establishment, no one gets to the world championship without first attempting a qualifying race. With no illusions whatsoever of magically making the start line at Kona on my first qualification attempt, I reasoned that my first Ironman event to enter should be geographically close by and popular (where many people I knew would be doing it as well), and where the goals I had set myself would be attained with reasonable effort.

Ironman triathlon is not for the faint of heart – there are sacrifices to be made on the long road to becoming a finisher, as thousands of Ironmen and Ironwomen will attest to. The investment of massive amounts of mileage is a pre-requisite, which entails time spent away from family, friends, and social occasions. At its core, it is a lonely race: Human interaction during the swim (where talking to other competitors is obviously not an option) is limited to bumping, kicking, and the occasional face-gouging or punch; bike drafting is outlawed; and the run is where everyone inevitably stews in their own private pot of pain and fatigue for long stretches of time. The journey to the start line and onwards to the finish line is strenuous - mentally and emotionally, if not physically.

I was duly informed of the perils of an Ironman race by the veterans who were my training buddies and triathlon acquaintances. The sheer repetitiveness of movement would fatigue muscles to the point of non-function for days afterwards, if not debilitating injury. How easy it was to lose concentration and cruise along in an almost zombie-like state, particularly on the marathon. Accident and injury horror stories aplenty, but also inspiring accounts of breakthrough performances, utter dedication to training, and toughing it out in the most trying of conditions. Come race day, I considered myself amply warned and familiar with what it took physically and - more importantly - mentally, to last the day and remain positive, no matter what the outcome would be.

The conditions on the swim were flawless, and coupled with a gigantic lane marker – the Busselton jetty itself – made the 3.8km swim leg very enjoyable. As soon as I got over the initial start line frenzy and found some open water, I quickly found my rhythm. I could feel the benefits of the consistent swim training I had had for the past seven months, and the numb hands and ‘ice cream headaches’ that used to plague my tropical constitution was but a distant memory, thanks to regular training swims in the cold waters of Port Phillip Bay. Three-quarters of the way through, I got kicked in the face and water filled my goggles, but I calmly rotated onto my back, re-adjusted them, and carried on. Apart from the occasional bumping and toe-tickling, I found it easy drafting other swimmers as well as letting them draft me, all the way to the swim exit.

I glanced at the timing clock as I trotted towards the transition tent, and was very surprised to see an elapsed time of 1 hour and 3 minutes! I was so pumped from seeing that that in the ensuing excitement, I scrambled out of T1 too quickly and accidentally cut myself on the chainring of my bike as I bumped into it. Ouch. Blood flowed freely from my ankle and dried to form a brownish-red crust on my left cycling shoe as I eased into the 180km ride along the picturesque coastal plains surrounding Busselton

The ride was a long - if flat - slog, but I was sure I had a consistent effort throughout. The jelly snakes I had knotted to my aerobars had dried up and were falling off as the morning heated up, but I had other food alternatives to rely on. The roads were rough in patches, but smooth in others, and the wind was quite tame throughout. I began to settle myself mentally for the long haul. Heaps of people on very flash bikes kept passing me, but I chose to stick to my game plan of racing my own race and keeping a high average cadence. My special needs bag, when I grabbed it from the roadside aid volunteers, was a highlight that brightened up the otherwise dull grind of the ride. It was a musette-style cloth bag from my university, and I carried it slung over my shoulder like a pro cyclist till the next aid station, refueling as I went. In retrospect, I think I rode a little too conservatively, but then again as this was the first time I was doing an Ironman, I wanted to remain comfortable with all muscles and joints intact, and with enough juice for the marathon.

Glad to be off my bike at T2, I got into the 42km run feeling sprightly… perhaps too sprightly. I found myself wondering why some of the competitors ahead of me, having collected a scrungy (indicating their completion of 1 lap of the run course) were walking when they could be going all out on the home stretch of a long day. Well, I was soon to find out.

Somewhere after I passed the half-marathon mark, I started to slow down, and the heat was becoming more than just a comfortable reminder of my sunny homeland. With temperatures soaring along the coastal running paths and a blazing afternoon sun sending glaring reflections off the waves by the beach, I regretted not wearing a cap or visor. I resorted to lashings of iced water over my head at every aid station to keep cool. I was physically in discomfort, and although I did not know it, my concentration was wandering as a result – the mind games had begun in earnest. I found it surprising, the amount of focus needed just to maintain a steady speed, let alone break stride and start walking. As this was my first-ever marathon (a lame excuse, but an excuse nonetheless!), experience was definitely not on my side; and while my mind was prepared for the ‘games’, I lacked that definitive mental edge that separates the veteran from the young gun.

Deep fatigue crept into my legs, and although I was certain I had taken enough electrolytes to stave off cramping, a dull pain soon established itself deep in my quadriceps. I sipped some Gatorade, but my stomach rebelled. Diluted with water and chased down with flat Coke though, it helped me through the last lap of the run. By this time, my whole running gait had regressed into a survival mode ‘shuffle’. It was definitely not cramps… more of muscles, joints, and connective tissues begging for mercy and an end to the continuous movement of running. Literally putting one foot in front of the other became a chore, I even ran in reverse for a short stretch. Finally, high on caffeine and the applause of the crowds lining the route, I trundled as best as I could into the finisher’s chute and into the waiting arms of the ‘catchers’. Medal and finisher’s towel draped around my sunburnt neck, I reflected upon the day’s work.

I had done it! I was an Ironman (so said the race commentator sitting high in his booth above the finish arch)! For the next couple of days, using staircases would be painful for me and fairly entertaining for people happening to watch me, but I had a wonderful experience to recount to all my friends.

To be continued… build-up, or burn-out?

Before I headed off to WA for the race, I asked my coach Simon what I should do training-wise to get fit for Coast to Coast. Noting the paucity of my kayak training leading into Ironman, he said: “We’re gonna have to paddle you like a madman”. Well, that and quite a bit more, actually. I had a relatively short recovery after WA, and considering I pulled up without any injury, considered myself extremely lucky… lucky enough to commit to a substantial build for the Longest Day of Coast to Coast, the next race on my calendar.

Prologue – Sizing Up

One race involves a mass open water swim, an 180km road bike time trial, and a full marathon, combined in a mind-boggling back-to-back format. The other boasts a backcountry course incorporating rural roads, mountain passes, and glacial rivers - spanning an island nation literally from coast to coast.

The Ironman triathlon and the Coast to Coast “Longest Day” multisport race: two endurance events, involving multiple disciplines, challenging the individual athlete, over a single day.

These two races are distinct from other well-known competitive endeavours of human endurance. There are single discipline events (like swimming the English Channel, ultramarathoning, and trans-ocean yacht racing) where total focus on a single skill set is required. There are the multi-day stage races (everything from week-long desert foot races to professional cycling tours like the Tour de France) that spread out the exertion over huge blocks of time, interspersed with sleep. And then there are team or relay events (as per adventure races and the hugely popular endurance mountain biking events) where an individual gets to be part of something more than just him/herself, and where the notion of “misery loves company” can be wholly realized.

Still, the Ironman and the Longest Day stand apart. They compress the fatigue and competition to within a single day, without rests or breaks – negating any opportunity to consolidate efforts or recover. They place the burden of the race effort upon the individual athlete – all the highs, lows, triumphs, and mistakes belong to him/her alone. And they demand that the single athlete – in order to just finish the race - be proficient across three disciplines and be able to make time cut-offs. These two events are truly the ultimate test in their respective endurance sports genres.

As an adventure racer on the look out for new challenges away from the team format for a change, I had always been intrigued to find out which race was the more difficult – the more grueling, arduous, and challenging. Only one way to find out: do them both.

Iron Will

The world championship for the Ironman race distance is held in Kona, on the big island of Hawaii, USA. As deemed by the triathlon establishment, no one gets to the world championship without first attempting a qualifying race. With no illusions whatsoever of magically making the start line at Kona on my first qualification attempt, I reasoned that my first Ironman event to enter should be geographically close by and popular (where many people I knew would be doing it as well), and where the goals I had set myself would be attained with reasonable effort.

Ironman triathlon is not for the faint of heart – there are sacrifices to be made on the long road to becoming a finisher, as thousands of Ironmen and Ironwomen will attest to. The investment of massive amounts of mileage is a pre-requisite, which entails time spent away from family, friends, and social occasions. At its core, it is a lonely race: Human interaction during the swim (where talking to other competitors is obviously not an option) is limited to bumping, kicking, and the occasional face-gouging or punch; bike drafting is outlawed; and the run is where everyone inevitably stews in their own private pot of pain and fatigue for long stretches of time. The journey to the start line and onwards to the finish line is strenuous - mentally and emotionally, if not physically.

I was duly informed of the perils of an Ironman race by the veterans who were my training buddies and triathlon acquaintances. The sheer repetitiveness of movement would fatigue muscles to the point of non-function for days afterwards, if not debilitating injury. How easy it was to lose concentration and cruise along in an almost zombie-like state, particularly on the marathon. Accident and injury horror stories aplenty, but also inspiring accounts of breakthrough performances, utter dedication to training, and toughing it out in the most trying of conditions. Come race day, I considered myself amply warned and familiar with what it took physically and - more importantly - mentally, to last the day and remain positive, no matter what the outcome would be.

The conditions on the swim were flawless, and coupled with a gigantic lane marker – the Busselton jetty itself – made the 3.8km swim leg very enjoyable. As soon as I got over the initial start line frenzy and found some open water, I quickly found my rhythm. I could feel the benefits of the consistent swim training I had had for the past seven months, and the numb hands and ‘ice cream headaches’ that used to plague my tropical constitution was but a distant memory, thanks to regular training swims in the cold waters of Port Phillip Bay. Three-quarters of the way through, I got kicked in the face and water filled my goggles, but I calmly rotated onto my back, re-adjusted them, and carried on. Apart from the occasional bumping and toe-tickling, I found it easy drafting other swimmers as well as letting them draft me, all the way to the swim exit.

I glanced at the timing clock as I trotted towards the transition tent, and was very surprised to see an elapsed time of 1 hour and 3 minutes! I was so pumped from seeing that that in the ensuing excitement, I scrambled out of T1 too quickly and accidentally cut myself on the chainring of my bike as I bumped into it. Ouch. Blood flowed freely from my ankle and dried to form a brownish-red crust on my left cycling shoe as I eased into the 180km ride along the picturesque coastal plains surrounding Busselton

The ride was a long - if flat - slog, but I was sure I had a consistent effort throughout. The jelly snakes I had knotted to my aerobars had dried up and were falling off as the morning heated up, but I had other food alternatives to rely on. The roads were rough in patches, but smooth in others, and the wind was quite tame throughout. I began to settle myself mentally for the long haul. Heaps of people on very flash bikes kept passing me, but I chose to stick to my game plan of racing my own race and keeping a high average cadence. My special needs bag, when I grabbed it from the roadside aid volunteers, was a highlight that brightened up the otherwise dull grind of the ride. It was a musette-style cloth bag from my university, and I carried it slung over my shoulder like a pro cyclist till the next aid station, refueling as I went. In retrospect, I think I rode a little too conservatively, but then again as this was the first time I was doing an Ironman, I wanted to remain comfortable with all muscles and joints intact, and with enough juice for the marathon.

Glad to be off my bike at T2, I got into the 42km run feeling sprightly… perhaps too sprightly. I found myself wondering why some of the competitors ahead of me, having collected a scrungy (indicating their completion of 1 lap of the run course) were walking when they could be going all out on the home stretch of a long day. Well, I was soon to find out.

Somewhere after I passed the half-marathon mark, I started to slow down, and the heat was becoming more than just a comfortable reminder of my sunny homeland. With temperatures soaring along the coastal running paths and a blazing afternoon sun sending glaring reflections off the waves by the beach, I regretted not wearing a cap or visor. I resorted to lashings of iced water over my head at every aid station to keep cool. I was physically in discomfort, and although I did not know it, my concentration was wandering as a result – the mind games had begun in earnest. I found it surprising, the amount of focus needed just to maintain a steady speed, let alone break stride and start walking. As this was my first-ever marathon (a lame excuse, but an excuse nonetheless!), experience was definitely not on my side; and while my mind was prepared for the ‘games’, I lacked that definitive mental edge that separates the veteran from the young gun.

Deep fatigue crept into my legs, and although I was certain I had taken enough electrolytes to stave off cramping, a dull pain soon established itself deep in my quadriceps. I sipped some Gatorade, but my stomach rebelled. Diluted with water and chased down with flat Coke though, it helped me through the last lap of the run. By this time, my whole running gait had regressed into a survival mode ‘shuffle’. It was definitely not cramps… more of muscles, joints, and connective tissues begging for mercy and an end to the continuous movement of running. Literally putting one foot in front of the other became a chore, I even ran in reverse for a short stretch. Finally, high on caffeine and the applause of the crowds lining the route, I trundled as best as I could into the finisher’s chute and into the waiting arms of the ‘catchers’. Medal and finisher’s towel draped around my sunburnt neck, I reflected upon the day’s work.

I had done it! I was an Ironman (so said the race commentator sitting high in his booth above the finish arch)! For the next couple of days, using staircases would be painful for me and fairly entertaining for people happening to watch me, but I had a wonderful experience to recount to all my friends.

To be continued… build-up, or burn-out?

Before I headed off to WA for the race, I asked my coach Simon what I should do training-wise to get fit for Coast to Coast. Noting the paucity of my kayak training leading into Ironman, he said: “We’re gonna have to paddle you like a madman”. Well, that and quite a bit more, actually. I had a relatively short recovery after WA, and considering I pulled up without any injury, considered myself extremely lucky… lucky enough to commit to a substantial build for the Longest Day of Coast to Coast, the next race on my calendar.